Practice Guidelines

At Genetic Support Foundation, our experts can help you navigate the increasingly complex array of genetic testing options and determine which tests are right for your patients.

Our free, comprehensive summaries of professional guidelines and policy statements on a wide range of timely genetic issues can help you quickly find the answers you need to support your patients and meet their genetic health needs.

Reproductive Health

There are more tests available during pregnancy than ever before, and navigating which of these newer tests to offer and when to offer them can be complicated. Many medical organizations have position statements that can provide guidance in this, but there can be subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) differences between them.

Our practice summaries provide helpful, expert summaries of the guidelines put forth by these various medical organizations to give you access to comprehensive guidelines in one place so you don’t need to waste valuable time tracking down the latest recommendations or sorting through different position statements.

Read on to learn more about practice guidelines for reproductive genetics.

Gene-by-gene carrier screening has been available for decades. Initially testing was available for a handful of relatively common autosomal recessive conditions that were associated with many health concerns and a shortened life expectancy. In recent years, next generation sequencing technology has allowed for screening of many genes at one time. Panels that screen for dozens to hundreds of genes associated with autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions are commonly called expanded carrier screening.

Several professional organizations have published practice guidelines and policy statements on carrier screening. These guidelines are catalogued here:

- The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)

- European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)

In general, each organization agrees:

- Decisions to have any form of carrier screening (i.e. single disorder or expanded carrier screen) should be voluntary and in the context of an informed decision.

- Educational materials that provide an overview of screening, the conditions screened for, and the benefits and limitations of testing should be available to all patients.

- Ideally carrier screening should be offered and, if desired by the patient, performed prior to pregnancy to maximize the number of reproductive options available.

- Information about carrier screening should be provided to every pregnant patient.

- If time constraints exist, screening of both the patient and the partner concurrently may be considered.

- Review of the benefits, limitations, and disadvantages of testing are essential elements of informed consent.

- Family history should be obtained prior to carrier screening to ensure appropriate carrier screening may be offered.

- If there is a family history of a genetic condition, referral to an appropriate genetics provider should be considered to ensure accurate risk assessment.

- Expanded carrier screening does not replace genetic counseling, and genetic counseling should be available to individuals prior to testing as desired

- If a carrier or carrier couple is identified, referral to genetic counseling is recommended to review results, additional testing available, reproductive options, and provide psychosocial support.

- Laboratories offering expanded carrier screening should abide by the following:

- Should follow the ACMG laboratory standards for classifying and reporting variants.

- Pathogenic variants reported must be validated, have clinical association, and be supported by further literature citations that report the variant as pathogenic (a single case citation is not sufficient).

Important considerations:

- Other methods of screening, such as enzyme analysis for Tay-Sachs disease, may have a higher detection rate than molecular testing.

- Carrier screening for some conditions may identify an increased risk of disease for the individual tested. Examples include:

- Identification of an individual with two pathogenic variants who has an autosomal recessive condition (such as Type 1 Gaucher disease or pseudocholinesterase deficiency, where an affected individual may not have clinical symptoms).

- Carrier with elevated risk, (such as a slightly elevated risk to develop Parkinson disease in carriers for Gaucher disease, or the increased risk for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome for fragile X premutation carriers).

- Carrier screening also has potential implications for the patient’s family members. If the patient is found to be a carrier for a genetic condition, their relatives may also have a higher chance to carry that same mutation.

Below we provide a brief ‘to the point’ summary from each organization. Click on one to get a more detailed breakdown of their position statement.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)

Committee Opinion 691 March 2017

The ACOG committee opinion stops short of endorsing expanded carrier screening, noting that ‘when selecting a carrier screening approach, the cost of each option to the patient and the healthcare system should be considered’. Rather, ACOG reiterates its recommendations to offer carrier screening for specific conditions, depending on risk as determined by ethnicity:

- Cystic fibrosis carrier screening should be offered to all women who are considering pregnancy or are currently pregnant.

- Complete analysis of the CFTR gene is not appropriate for routine carrier screening and should be reserved for individuals with suspicion based on personal or family history of the condition.

- Spinal muscular atrophy carrier screening should be offered to all women who are considering pregnancy or are currently pregnant.

- A complete blood count (CBC) should be performed in all women who are currently pregnant to assess for the possibility of hemoglobinopathies.

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis should be performed for those with of African, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Southeast Asian, or West Indian descent.

- Solubility tests alone (e.g. “Sickledex”) are inadequate for diagnosis of sickle cell disorders and should not be utilized as a first-line carrier screen.

- Fragile X carrier screening should be offered to women who are considering pregnancy or are currently pregnant with a family history suggestive of fragile X syndrome.

- This includes women with a family history of conditions suggestive of Fragile X syndrome including intellectual disability and unexplained ovarian insufficiency or failure, or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40.

- Individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, should be offered carrier screening for Canavan disease, cystic fibrosis, familial dysautonomia, and Tay-Sachs disease.

- Further screening for Bloom syndrome, familial hyperinsulinism, fanconi anemia, gaucher disease, glycogen storage disease type 1, joubert syndrome, maple syrup urine disease, mucolipidosis type IV, niemann-pick disease, and usher syndrome may also be considered.

- Tay-Sachs carrier screening should be offered to all women who are considering or are currently pregnant if either member of the couple is of Ashkenazi Jewish, French Canadian, or Cajun.

American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG)

ACMG recommends that all patients who are pregnant or considering pregnancy be offered reproductive carrier screening. They outline a recommended panel of 113 genes associated with autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions based on population carrier frequency and condition severity. For consanguineous couples, they recommend consideration of a more extensive panel. Currently there are no testing laboratories that offer a panel inclusive of all 113 genes outlined by the ACMG. Carrier screening is optional and should not be considered routine. Pre-test and post-test genetic counseling is recommended with specific points of discussion outlined in the guideline.

ESHG Policy Statement

Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening March 2016

ESHG recognizes and outlines the challenges that expanded carrier screening brings to routine clinical care. The aim of the ESHG policy statement is to outline clinical and laboratory guidelines for use with expanded carrier screening, taking into account lessons learned from the history of screening programs for single gene disorders.

Noninvasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) through analysis of cell free DNA (cfDNA) was first introduced in 2011 as a screening test for Down syndrome (trisomy 21). The list of conditions that cfDNA can screen for has grown to include trisomy 18, trisomy 13, sex chromosome conditions, several microdeletion conditions, and more recently some single gene conditions. Several professional organizations have published practices guidelines and statements regarding cfDNA including:

- The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)

- The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM)

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC)

- The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)

- The American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG)

ALL guidelines advocate the following

- Patients should have the opportunity to make an informed choice to decline or accept testing

- Pre and post-test counseling regarding the overall benefits, risks, and limitations is essential

Other important guideline information:

- In 2020, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists partnered with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine to update the guideline “Screening for Fetal Chromosomal Abnormalities”, Practice Bulletin 226. In this guideline, ACMG and SMFM recommend that “prenatal genetic screening (serum screening with or without nuchal translucency ultrasound -or- cell-free DNA screening) and diagnostic testing (CVS or amniocentesis) options should be discussed and offered to all pregnant patients regardless of age or risk for chromosomal abnormality. After review and discussion, every patient has the right to pursue or decline prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing.”

- In 2016, ACMG updated their cfDNA policy: ‘New evidence strongly suggests that NIPS can replace conventional screening for Patau, Edwards, and Down syndromes across the maternal age spectrum, for a continuum of gestational age beginning at 9–10 weeks, and for patients who are not significantly obese.’

- The ISPD discourages the use of maternal age as an indicator of prior risk and states that cfDNA is one possible primary screening approach for women, regardless of age or other risk factors.

Below we provide a brief ‘to the point’ summary from each organization. Click on one to get a more detailed breakdown of their position statement.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) and Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine

To the point…

In 2020, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists partnered with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine to update the guideline “Screening for Fetal Chromosomal Abnormalities”, Practice Bulletin 226. In this guideline, ACMG and SMFM recommend that “prenatal genetic screening (serum screening with or without nuchal translucency ultrasound -or- cell-free DNA screening) and diagnostic testing (CVS or amniocentesis) options should be discussed and offered to all pregnant patients regardless of age or risk for chromosomal abnormality. After review and discussion, every patient has the right to pursue or decline prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing.”

ACOG and SMFM emphasize the importance of counseling and education about testing options and for autonomous decision making about whether to undergo prenatal screening and diagnosis, “all patients have the right to accept or decline testing after counseling.”

The recommend AGAINST using multiple screening modalities for aneuploidy.

Patients with “no-call” or unreportable results should be informed about the association of higher probability of aneuploidy with no-call results and they should be offered genetic counseling, ultrasound and consideration of diagnostic testing.

ACOG states that all screening modalities are less accurate in twin pregnancies, however they do state that cfDNA can be performed in twin pregnancies.

American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG)

To the point…

The ACMG published a Statement on Noninvasive Prenatal Screening for aneuploidy. Unlike other professional organizations, ACMG does not recommend that cfDNA be restricted to women at increased risk. ACMG emphasizes that cfDNA should not be considered a routine prenatal test, as well as the importance of pre- and post-test counseling. There are specific scenarios in which cfDNA is not considered the best option (i.e. a case of fetal anomalies that is suggestive of a single gene disorder). The guideline states that cfDNA does not replace the need for first trimester ultrasound or maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein in the second trimester as screening for neural tube defects. There are a number of patient resources references in this guideline.

National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC)

To the point…

The NSGC currently supports the use of cfDNA as an option for pregnant patients. NSGC advocates that qualified providers should communicate the benefits and limitations of cfDNA screening to patients prior to testing and because many factors influence cfDNA screening performance it may not be the most appropriate option for every pregnancy. Prior to undergoing cfDNA screening, patients should have the opportunity to meet with qualified providers who can facilitate an individualized discussion of patient’s values and needs including the option to decline all screening or proceed directly to diagnostic testing. Patients whose cfDNA results indicate increased-risk should receive post-test genetic counseling from clinicians with expertise in prenatal screening, such as genetic counselors, and be given the option of diagnostic testing to facilitate informed decision making.

American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) & European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)

To the point…

The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) and the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) released a joint statement on cfDNA in March 2015. Similar to other organizations the ESHG/ASHG statement emphasizes the cfDNA is a screening test and the importance of pretest information and counseling is highlighted. Many ethical issues of the expanding role of cfDNA to include condition such as microdeletions and sex chromosome conditions are discussed in detail and ultimately the statement advises against the use of cfDNA for conditions apart from trisomy 21, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13.

Traditionally, genetic counselors in prenatal care interface with patients only after they have been determined to be “high risk” due to family history concerns or tests such as carrier screening, aneuploidy screening, and ultrasound. However, the current state of obstetrical care involves complex choices involving genetic testing for all pregnant women. The testing options available to women will only continue to grow with the expansion of new technology, and it is paramount that service delivery models adapt to the increasing complexity of genetic testing choices.

Most healthcare delivery models do not support services that allow women to make informed and value-consistent decisions about the growing array of available prenatal tests. Many in the field of obstetrics are recognizing the need for qualified experts to help patients navigate their options as genetic testing for all pregnant women continues to expand.

We are often asked, “but are there enough genetic counselors?” It is likely impossible at this time to have every pregnant woman access one-on-one genetic counseling services. However, there are creative ways to support patients and OB providers to optimize the patient experience and ensure that patients are making the best choices regarding genetic tests to meet their needs.

Prenatal genetic testing is typically used for reproductive planning and is intensely personal. While some women find the information that prenatal testing provides to be helpful for preparation or making decisions about pregnancy termination, some women feel very opposed to this information. We have done audits of prenatal genetic screening practices and have seen that in some cases 100% of patients undergo screening in one doctor’s office, whereas 0% of patients undergo screening when seen by the provider down the hall.

So what is appropriate uptake for these optional tests? The answer is that there is no ‘appropriate’ percentage. If one were to aim for either 100% or 0% genetic testing uptake, then our responsibility to support patients as they make informed, autonomous, and value-consistent decisions is likely being overlooked. The percentage of patients that we have in a given time period that choose to undergo genetic testing will likely vary when comparing different time periods because individual decisions about this very personal topic are variable by nature.

The challenges to informed consent in the current prenatal care model are numerous and complex. Given the pace of change in the fields of genetics, it is not surprising that the healthcare providers (obstetricians, midwives, family medicine physicians, and their staff) tasked with discussing prenatal genetic tests often lack the expertise to obtain informed consent for these complex testing options. The current state of prenatal care often leads OB providers to recommend or encourage testing for their patients rather than to support individual choices through shared-decision support. Limited time and expertise coupled with a background of concern for a wrongful life suit are factors that may lead to favoring testing, even if it is not in the best interest of the patient based on their individual needs and values.

Genetic Support Foundation wants to change the way that women and couples are provided with information about prenatal genetic testing. One aspect of achieving this goal is developing and implementing standardized education programs for primary obstetrical care. Such programs can enable more informed decisions and reduce healthcare costs by supporting optimal utilization of testing.

Standardized genetic education may come in the form of online tools, such as our animated videos that review prenatal testing options, but also may be print materials, in-person classes, or webinars.

At Genetic Support Foundation, we are committed to developing tools to optimize education about optional genetic tests so that patients can be empowered to make the decisions that are best for them. Contact us for more information about additional ways to deliver prenatal genetic testing information.

Oncology

Criteria for who meets medical guidelines for genetic testing is constantly evolving. GSF makes this process easier for you by providing helpful summaries of the referral guidelines for genetic counseling as set forth by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN is a non-profit organization comprised of representatives from 27 of the leading centers which come together to make recommendations regarding the diagnosis and treatment of various types of cancer.

As part of their mission to improve the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of cancer care, NCCN also works to determine the circumstances in which genetic testing should be considered. Some insurances also require that the patient meet with a genetic counselor or other qualified genetics provider prior to covering testing.

Read on to learn more about NCCN guidelines for when to refer patients for genetic counseling for hereditary cancer predisposition.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v 1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Breast Cancer

- Breast cancer diagnosed at or before age 50

- Triple-negative breast cancer

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry

- Male breast cancer

- A mutation identified on tumor genomic testing that has clinical implications if also identified in the germline

- Multiple primary breast cancers

- To aid in treatment decisions (PARP inhibitors in the metastatic setting or adjuvant treatment decisions with olaparib for high-risk, HER2 negative breast cancer)

- Lobular breast cancer with personal or family history of diffuse gastric cancer

- Family history of breast cancer at or before age 50, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer with metastatic or high/very high risk group, 3 or more total breast cancers, 2 or more close relatives with either breast or prostate cancer

Family History of Breast Cancer

- A family history of breast cancer diagnosed at or before age 50

- A family history of triple-negative breast cancer

- A family history of breast cancer AND a family history of ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancer

- A family history of three or more women on the same side of the family with breast cancer

- A family history of male breast cancer

- An affected or unaffected individual who has a probability of greater than 5% of a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant based on prior probability models (eg, Tyrer-Cuzick, BRCAPro, Pennll)

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

Post-Test Counseling

- With a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant

- Negative results but tumor profiling, personal history, or family history remain suggestive of an inherited condition

- Any VUS results for which a provider considers using to guide management

- A mosaic or possibly mosaic result

- Discrepant interpretation of variants, including discordant results across laboratories

- Interpretation of personal risk score, if they are being used in clinical management

- Interpretation of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants for patients tested through direct-to-consumer or consumer-initiated models

*Referral is also clinically indicated for individuals meeting criteria but with previous limited testing (eg, single gene or absent deletion/duplication analysis) interested in pursuing multi-gene testing

Conditions to Consider

- ATM-related cancer susceptibility

- BRCA-related cancer susceptibility

- CDH1-related cancer susceptibility

- CHEK2-related cancer susceptibility

- NBN-related cancer susceptibility

- NF1-related cancer susceptibility

- PALB2-related cancer susceptibility

- PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

- TP53-related cancer susceptibility

Recommended Genetic Testing

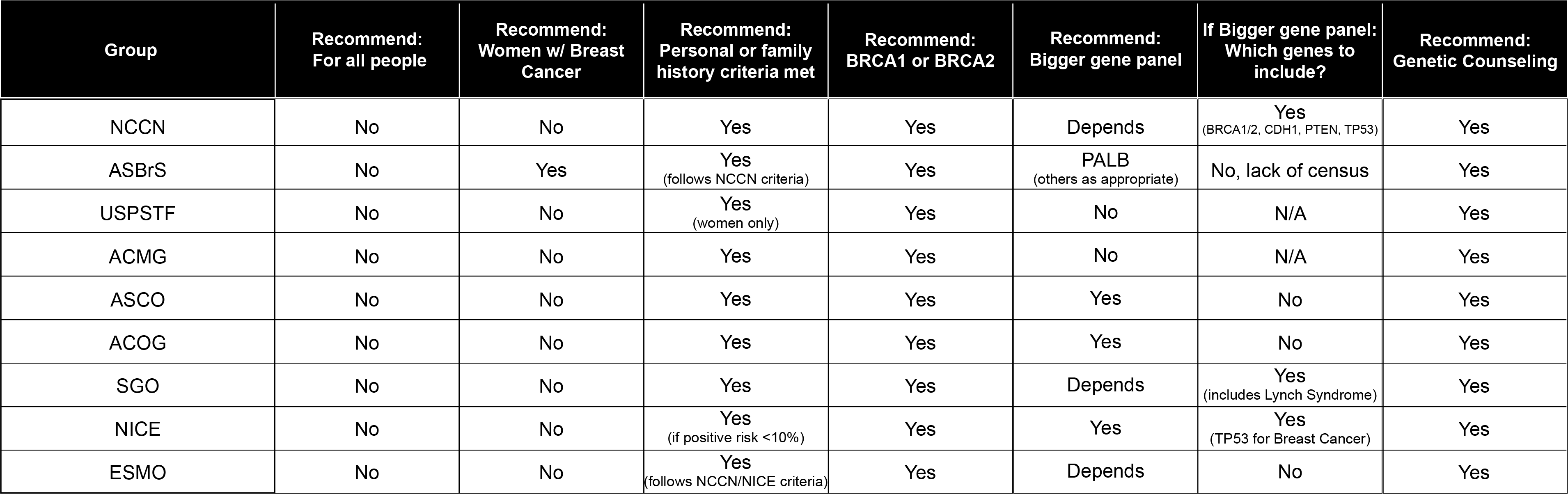

All guidelines advocate the following

- Patients should have the opportunity to make an informed choice to decline or accept testing

- Pre- and post-test counseling regarding the overall benefits, risks, and limitations is essential

- Post-test counseling should include risk reduction strategies

Other important guideline information

- Genetic testing should first be performed in an affected family member whenever possible

- Following testing, it is also important to have experts available to interpret results and recommend treatment planning, ideally as part of a multidisciplinary team of providers

- Treatment should not be based on variants of uncertain significance

- Family histories change over time and should be reassessed periodically

- Patients tested before 2014 should be considered for updated testing

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022 and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Uterine Cancer

- Uterine cancer diagnosed before the age of 50

- Uterine cancer diagnosed at any age with tumor showing evidence of mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency, either by microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR protein expression

- A history of uterine cancer and another synchronous or metachronous Lynch syndrome-related cancer**

- Uterine cancer diagnosed at any age with one or more first- or second-degree relative diagnosed with Lynch syndrome-related cancer** before the age of 50

- Uterine cancer diagnosed at any age with two or more first- or second-degree relatives diagnosed with Lynch syndrome-related cancers** regardless of age

Family History of Uterine Cancer

- One or more first-degree relative with colorectal or uterine cancer diagnosed before age 50

- One or more first degree relative with colorectal or uterine cancer and another synchronous or metachronous Lynch syndrome-related cancer**

- Two or more first- or second-degree relatives with Lynch syndrome-related cancer**, including one or more diagnosed before age 50

- Three or more first- or second-degree relatives with Lynch syndrome-related cancers**, regardless of age

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

- Increased model-predicted risk for Lynch syndrome

- An individual with a 5% or greater risk of having an MMR gene pathogenic variant based on predictive models (ie, PREMM5, MMRpro, MMRpredict)

**Lynch syndrome-related cancers include colorectal, endometrial, gastric, ovarian, pancreas, ureter and renal pelvis, brain (usually glioblastoma), biliary tract, small intestinal cancers, as well as sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas as seen in Muir-Torre syndrome

Conditions to Consider

- EPCAM-related cancer susceptibility

- MLH1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH2-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH6-related cancer susceptibility

- PMS2-related cancer susceptibility

- POLD1-related cancer susceptibility

- PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

- TP53-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022 and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Colon Cancer

- Colon cancer diagnosed at or before age 50

- Colon cancer at any age AND any of the following

- Tumor showing mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency, either by microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR protein expression

- Tumor with MSI-high (MSI-H) histology (ex presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn’s like lymphocytic reaction, mucinous/signet ring differentiation, or medullary growth pattern)

- Personal history of synchronous or metachronous Lynch syndrome related cancer**

- One or more first or second-degree relative with a Lynch syndrome related cancer** diagnosed before age 50.

- Two or more first or second-degree relative with a Lynch syndrome related cancer** diagnosed at any age.

- Increased model-predicted risk for Lynch syndrome

- An individual with a 5% or greater risk of having an MMR gene pathogenic variant based on predictive models (ie, PREMM5, MMRpro, MMRpredict)

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

- Genetic counseling/patient education is highly recommended when genetic testing is offered and when results are disclosed.

- If no pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is found, consider referral for expert genetics evaluation if not yet performed; testing for other hereditary cancer syndromes may be appropriate.

- Consider evaluation in all individuals with colorectal cancer (category 2B)

Family History of Colon Cancer

- One or more first-degree relatives with colorectal or uterine cancer diagnosed before age 50

- One or more first-degree relatives with colorectal or uterine cancer and another synchronous or metachronous Lynch syndrome-related cancer**

- Two or more first or second-degree relatives with Lynch syndrome-related cancer**, including > 1 relatives diagnosed before age 50

- Three or more first or second-degree relatives with Lynch syndrome-related cancers, regardless of age

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

- Increased model-predicted risk for Lynch syndrome

- An individual with a 5% or greater risk of having an MMR gene pathogenic variant based on predictive models (ie, PREMM5, MMRpro, MMRpredict)

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

- Genetic counseling/patient education is highly recommended when genetic testing is offered and when results are disclosed.

**Lynch syndrome-related cancers include colorectal, endometrial, gastric, ovarian, pancreas, ureter and renal pelvis, brain (usually glioblastoma), biliary tract, small intestinal cancers, as well as sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas as seen in Muir-Torre syndrome

Conditions to Consider

- APC-related cancer susceptibility

- AXIN2-related cancer susceptibility

- BMPR1A-related cancer susceptibility

- CHEK2-related cancer susceptibility

- EPCAM-related cancer susceptibility

- GALNT12-related cancer susceptibility

- GREM1-related cancer susceptibility

- MLH1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH2-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH3-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH6-related cancer susceptibility

- MUTYH-related cancer susceptibility

- NTHL1-related cancer susceptibility

- PMS2-related cancer susceptibility

- POLD1-related cancer susceptibility

- POLE-related cancer susceptibility

- PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

- Serrated polyposis syndrome

- SMAD4-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

- TP53-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022 and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with personal or family history of one or more of the following:

Adenomas

- 10 or more Adenomas

- Any number of adenomas with personal history of desmoid tumor, hepatoblastoma, cribriform-morular variant of papillary thyroid cancer, or multifocal/bilateral Congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)

Hamartomas

- Two or more hamartomatous polyps

- Consider referral for fewer hamartomas if present with any of the following:

- Mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation of the mouth, lips, nose, eyes, genitalia, or fingers.

- PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome related featuresᅀ.

Serrated Polyps

- Includes hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, serrated adenomas

- Size and location

- 5 or more serrated polyps proximal to the rectum, all being 5mm in size or greater with 2 or more being 10mm in size or greater

- 20 or more serrated polyps of any size distributed throughout the colon, with 5 or more being proximal to the rectum

- Any number of serrated polyps if family history of serrated polyposis in first degree relative

Juvenile Polyps

- 5 or more juvenile polyps in colon

- Multiple juvenile polyps throughout GI tract

- Any number of juvenile polyps in individuals with a family history of Juvenile polyposis syndrome

Other/Family History

- Family history of any blood relative with a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene

- Genetic counseling/patient education is highly recommended when genetic testing is offered and when results are disclosed.

- If no pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant is found, consider referral for expert genetics evaluation if not yet performed; testing for other hereditary cancer syndromes may be appropriate.

ᅀ PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome related features can include breast cancer, endometrial cancer, follicular thyroid cancer, ganglioneuromas, macrocephaly, macular pigmentation of glans penis, trichilemmomas, multiple palmoplantar keratosis, multifocal or extensive oral mucosal papillomatosis, multiple cutaneous facial papules, autism, colon cancer, >3 esophageal glycogenic acanthosis, lipomas, intellectual disability (IQ < 75, thyroid lesions (adenomas, nodules, goiter), renal cell carcinoma, testicular lipomatosis, and/or vascular anomalies.

Conditions to Consider

- APC-related cancer susceptibility

- AXIN2-related cancer susceptibility

- BMPR1A-related cancer susceptibility

- GREM1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH3-related cancer susceptibility

- MUTYH-related cancer susceptibility

- NTHL1-related cancer susceptibility

- POLD1-related cancer susceptibility

- POLE-related cancer susceptibility

- PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

- RNF43-related cancer susceptibility

- SMAD4-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Gastric Cancer

- An individual affected with gastric cancer before age 40

- An individual affected with gastric cancer before age 50 who had one first- or second-degree relative affected with gastric cancer

- An individual affected with gastric cancer at any age who has 2 or more first- or second-degree relatives affected with gastric cancer

- An individual affected with gastric cancer and breast cancer with one diagnosis before age 50

- An individual affected with gastric cancer at any age and a family history of breast cancer in a first- or second-degree relative diagnosed before age 50

- An individual affected with gastric cancer at any age and family history of juvenile polyps or gastrointestinal polyposis

- An individual affected with gastric cancer at any age and family history of cancers associated with Lynch syndrome (colorectal, endometrial, small bowel, or urinary tract cancer)

Family History of Gastric Cancer

- Known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a gastric cancer susceptibility gene in a close relative

- Gastric cancer in one first- or second-degree relative who was diagnosed before age 40

- Gastric cancer in two first- or second-degree relative with one diagnosis before age 50

- Gastric cancer in three first- or second-degree relatives independent of age

- Gastric cancer and breast cancer in one patient with one diagnosis before age 50, juvenile polyps, or gastrointestinal polyposis in a close relative

Conditions to Consider

-

- APC-related cancer susceptibility

- BMPR1A-related cancer susceptibility

- CDH1-related cancer susceptibility

- EPCAM-related cancer susceptibility

- MLH1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH2-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH6-related cancer susceptibility

- PMS2-related cancer susceptibility

- SMAD4-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022 and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Ovarian Cancer

- Epithelial ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube cancer or peritoneal cancer) at any age

Family History of Ovarian Cancer

- First- or second-degree relative with epithelial ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube cancer or peritoneal cancer) at any age

- An individual with a 5% or greater probability of a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant based on prior probability models (eg Tyrer-Cuzick, BRCAPro, CanRisk)

*Referral is also clinically indicated for individuals meeting criteria but with previous limited testing (eg, single gene or absent deletion/duplication analysis) interested in pursuing multi-gene testing

Conditions to Consider

- BRCA-related cancer susceptibility

- BRIP1 related cancer susceptibility

- DICER1 related cancer susceptibility (Non-epithelial ovarian cancers)

- EPCAM-related cancer susceptibility

- MLH1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH2-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH6-related cancer susceptibility

- PMS2-related cancer susceptibility

- RAD51C-related cancer susceptibility

- RAD51D-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility (Non-epithelial ovarian cancers)

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v2.2022, v1.2022, and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Pancreatic Cancer

- Exocrine pancreatic cancer diagnosed at any age

- Pancreatic or duodenal neuroendocrine tumor at any age

Family History of Pancreatic Cancer

- First--degree relative with exocrine pancreatic cancer or neuroendocrine tumor diagnosed at any age

*Referral is also clinically indicated for individuals meeting criteria but with previous limited testing (eg, single gene or absent deletion/duplication analysis) interested in pursuing multi-gene testing

Conditions to Consider

- ATM-related cancer susceptibility

- BRCA-related cancer susceptibility

- CDKN2A-related cancer susceptibility

- EPCAM-related cancer susceptibility

- MLH1-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH2-related cancer susceptibility

- MSH6-related cancer susceptibility

- PALB2-related cancer susceptibility

- PMS2-related cancer susceptibility

- STK11-related cancer susceptibility

- TP53-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Prostate Cancer

- Metastatic prostate cancer at any age

- High- or Very-high-risk group prostate cancer

- With family history or ancestry

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry

- One or more close relative with:

- Breast cancer at or before age 50

- Triple negative breast cancer at any age

- Ovarian cancer at any age

- Pancreatic cancer at any age

- Metastatic or high- or very-high-risk group prostate cancer at any age

- Two or more close relatives with breast or prostate cancer (any grade) at any age

- May be considered in individuals with intermediate-risk prostate cancer with intraductal/cribriform histology at any age

Family History of Prostate Cancer

- A first-degree relative with metastatic or High- or Very-high-risk group prostate cancer at any age

- A first-degree relative with prostate cancer and:

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry; or

- One or more close relative with: Breast cancer at or before age 50, Triple negative breast cancer at any age, Ovarian cancer at any age, Pancreatic cancer at any age, or Metastatic or high- or very-high-risk group prostate cancer at any age

- Two or more close relatives with breast or prostate cancer (any grade) at any age

*Referral is also clinically indicated for individuals meeting criteria but with previous limited testing (eg, single gene or absent deletion/duplication analysis) interested in pursuing multi-gene testing

Conditions to Consider

- BRCA-related cancer susceptibility

- HOXB13-related cancer susceptibility

- PALB2-related cancer susceptibility

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN v3.2022 and v1.2023) guidelines recommend referral to a cancer genetics professional for an individual with one or more of the following:

Affected with Thyroid Cancer

- Medullary thyroid cancer at any age

- Follicular or papillary thyroid cancer, or thyroid structural lesions (adenoma, nodule, goiter) with other criteria for PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

ᅀ PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome related features can include breast cancer, endometrial cancer, follicular thyroid cancer, ganglioneuromas, macrocephaly, macular pigmentation of glans penis, trichilemmomas, multiple palmoplantar keratosis, multifocal or extensive oral mucosal papillomatosis, multiple cutaneous facial papules, autism, colon cancer, >3 esophageal glycogenic acanthosis, lipomas, intellectual disability (IQ < 75, thyroid lesions (adenomas, nodules, goiter), renal cell carcinoma, testicular lipomatosis, and/or vascular anomalies.

Conditions to Consider

- APC-related cancer susceptibility

- Carney complex

- DICER1 related cancer susceptibility

- Familial Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (FMTC)

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN2A)

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN2B)

- PTEN-related cancer susceptibility

- Li Fraumeni syndrome

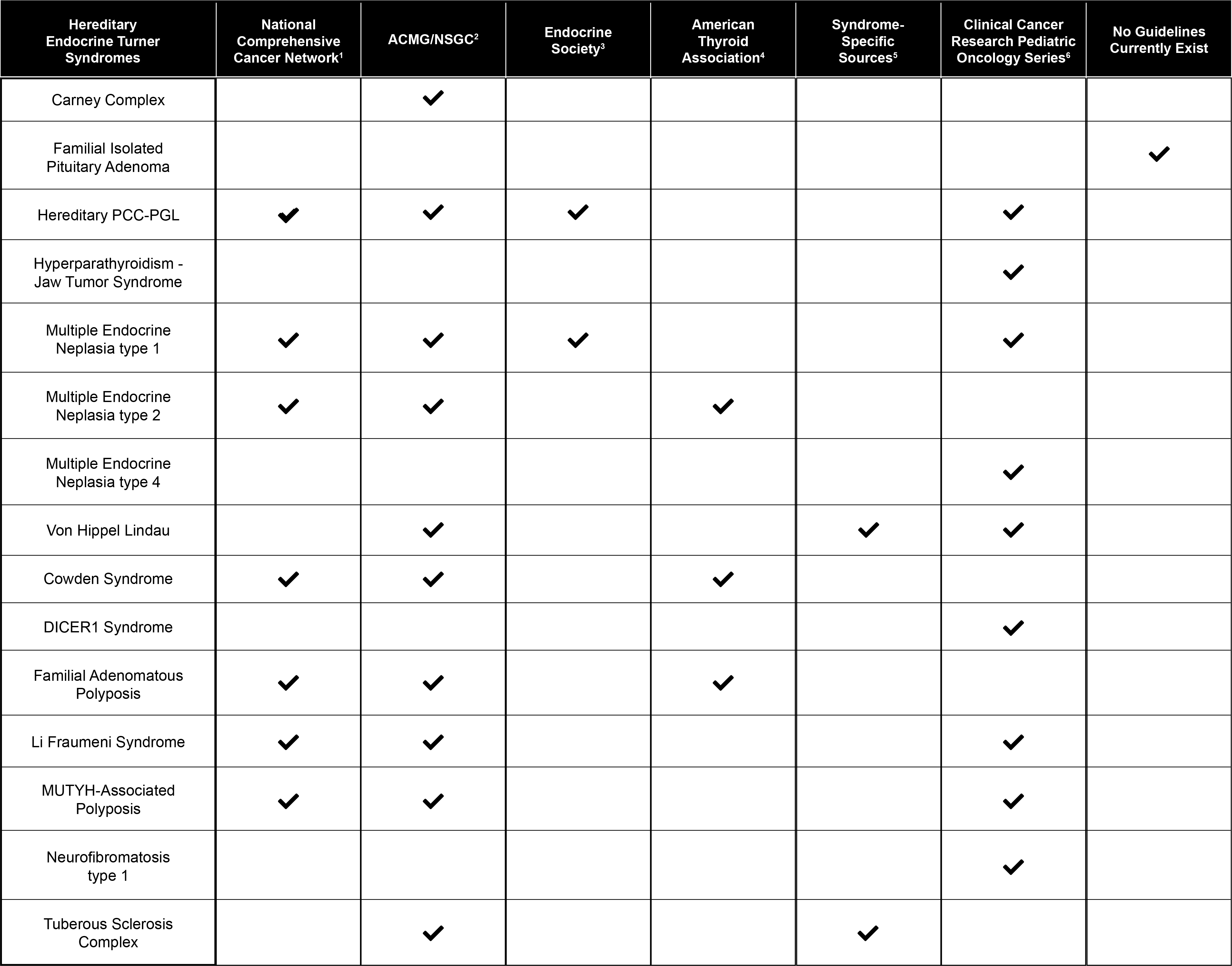

Adapted from Brock et al., 2020 Endocrine Related Cancer: Challenges and opportunities in genetic counseling for hereditary endocrine neoplasia syndromes.

Despite the ever-increasing scientific literature in genetics/genomics and in the sub-specialty of hereditary endocrine neoplasia syndromes, the publication of comprehensive and consolidated genetic counseling resources for endocrine cancer predisposition has lagged behind other hereditary cancer indications. The varied resources are spread across different journals, consortia, and professional societies (table below). In addition to the challenges of finding appropriate resources, there is also heterogeneity among recommendations put forth for genetic evaluation and/or testing in these conditions. Genetic evaluation and testing guidelines also provide varying levels of detail regarding referral criteria. For example, many publications do not specify whether age at presentation plays into the genetic evaluation referral criteria, or provide guidance regarding age at which genetic evaluation should be considered.

Current Professional Society Guidelines for Genetic Evaluation and/or Testing:

1Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors (Version 1.2019), Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal (Version 1.2018), Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian (Version 3.2019)

2Hampel et al., 2015 (PMID: 25394175)

3Thakker et al., 2012 (PMID: 22723327), Lenders et al., 2014 (PMID: 24893135)

4Wells et al., 2015 (PMID: 25810047), Haugen et al., 2016 (PMID 26462967)

5International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference, 2013 (PMID: 24053983), VHL Alliance, 2019 Suggested Referral Criteria for VHL Clinical Care Centers

6Wasserman et al., 2017 (PMID: 28674121) , Rednam et al., 2017 (PMID: 28620007), Achatz et al., 2017 (PMID: 28674119), Evans et al., 2017 (PMID: 28620004), Schultz et al., 2017 (PMID: 28620008)