Cancer & Genetics

A family history of cancer is scary. Our genetic counselors help families understand their risks.

Some people have a higher risk for cancer due to inherited genetic mutations. Recognizing this risk can allow for earlier detection and even prevention of some cancers. Are you concerned about cancer in your family?

Genetic counseling and testing can help you determine if you or others in your family may have an inherited genetic risk for cancer and help guide you through the process of screening and medical management for individuals at higher risk.

Understanding Hereditary Cancer & Genetic Testing

Cancer is unfortunately very common, affecting approximately 1 in 2 men and 1 in 3 women during their lifetime. Although most cancers are not inherited, some families do have a higher risk for cancer than others. Genetic counseling and testing can help determine if there may be an inherited genetic risk for cancer in your family and who in your family is at higher risk for cancer. It can also help guide the appropriate screening and medical management for individuals at higher risk.

Here we discuss the connection between genes and cancer, provides an overview of the genetic testing process, and touches on some important considerations when deciding whether or not to pursue cancer genetic testing.

Research over the past few decades has shown that genes play a key role in the development and behavior of cancers. In short, genes are the instructions that tell our cells how to grow and function to keep us healthy. Therefore, changes within those instructions can cause cells to lose their regulation and grow out of control, leading to a tumor.

The majority of cancers are sporadic, or occur just by chance. Within cancer cells, genetic mutations are found that are different from the healthy, non-cancerous cells in the body. As noted above, these genetic mutations are understood to cause and influence the abnormal growth of the cancer cells. Typically, sporadic cancers occur in people when they are older, and there is not a strong pattern of cancer within the family (although because cancer is common, it is not unusual to have some history of cancer in the family). The causes for sporadic cancers are largely unknown, but may include environmental and lifestyle risk factors (e.g. smoking, UV exposure) as well as the natural and unavoidable process of aging.

In about 5-15% of cancers, the underlying cause is due to an inherited gene mutation that increases the risk to develop certain types of cancer during the lifetime. An inherited mutation (passed from parent to child) is present from conception and is found in every cell of the body. Although by itself the mutation is not cancerous, it increases the chance for other random mutations to occur and accumulate in the cells, leading to the development of cancer.

Here are some things that may indicate that someone has a higher risk for hereditary cancer:

- early-onset cancers (i.e. diagnosed before the age of 50 years),

- individuals with multiple primary cancers (i.e. 2 or more cancers of separate origin, not the spread of one cancer to other areas of the body)

- rare types of cancer (i.e. ovarian)

- family history of the same type or related types of cancers in multiple individuals and generations

- persons from certain ancestral backgrounds (e.g. Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry) have a higher chance to carry mutations common to those populations

- a known pathogenic variant in a cancer risk gene has been previously identified in a relative

A third category for classifying cancer risk is familial cancer. These descriptions may be used when there appears to be more cancer in a family than we would expect by chance alone, but the cause is not identified. There may be a combination of multiple genetic and/or environmental risk factors that are increasing the risk for cancer in the family, or there could be a genetic cause for the cancer that has not yet been identified. Therefore, until more clear answers can be found, the most important message is that the family should be considered at some level of increased cancer risk, and be managed based on their unique history.

Genetic testing for hereditary cancer first starts with a genetic consultation to collect and analyze the personal and/or family history of cancer. If a pattern suggestive of hereditary cancer is identified, then genetic testing may be considered for further clarification or confirmation of the specific cancer risks.

Depending on the history, it may be recommended that a specific individual in the family is the first to undergo the genetic testing. Whenever possible, it is recommended to initiate testing in a family member who has had a diagnosis of cancer most suggestive of hereditary causes, since this is the most likely person to have a mutation identified through the testing. However, we understand that this is not always possible, such as when the family member is deceased or is otherwise unable or unwilling to undergo the testing.

If a cancer-associated gene mutation has previously been identified in the family, then testing can be targeted to that specific mutation with the ability to definitively confirm or rule out increased risk. If no prior testing has been done, then genetic testing may include one or a few specific genes that are strongly suspected based on the history. Alternatively, in some cases, more broad panels to include testing of multiple genes may be considered.

To help understand the possible results, it is important to have a brief background about what genetic testing looks for. Each of our genes is made up of a string of thousands of letters. These letters make up an instruction manual for how to build a protein, and the proteins are what is actually making our body function how it should. Genetic testing generally looks at genes through sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis. Most of the genes that we associate with hereditary cancer risk make proteins that help our bodies prevent various types of cancer from forming.

My Results are Positive - What does that mean?

A positive result (may also be called ‘mutation detected’) confirms inherited risk for cancer in the person who was tested. A mutation means that the lab found either a spelling error (by sequencing), or missing or extra letters (by deletion/duplication studies) that we know make the instructions for that gene incorrect. If the instructions are incorrect, then that gene will either not produce a protein, or will produce a protein that doesn’t do what it is supposed to. In the case of hereditary cancer genes, if they are not producing a protein, or are producing a protein that doesn’t function properly, these non-working genes can cause an increased risk for related types of cancer.

Each gene is related to different types of cancer. Therefore, if someone has a mutation in a gene related to hereditary cancer, identifying which gene the mutation is in can tell us what forms of cancer someone may be at risk for, and how high that risk is. Once we know that someone is at an increased genetic risk for cancer, appropriate high-risk screening and management options should be discussed.

Finding out that someone carries a gene mutation associated with an increased risk for hereditary cancer means that their relatives may also be at an increased risk. Most of these genes are passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that if someone carries a gene mutation, there is a 50% risk for first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) to also carry it. If we have an identified familial gene mutation, then we can use that information to offer testing to family members to determine who may also have a higher hereditary risk for cancer. If relatives are also found to carry this gene mutation, then recommendations can be made for high-risk screening and management. If relatives are found to not carry the gene mutation, then we can reassure them that they should have a risk for cancer that is similar to those in the general population.

My Results are Negative - What does that mean?

There are actually two different type of negative test results when it comes to hereditary cancer genetic testing: a true negative and an uninformative negative.

An uninformative negative rules out all mutations detectable by the particular test performed. The lab screens for mutations by looking for harmful spelling errors in the gene (by sequencing) or missing or extra letters (by deletion/duplication studies). An uninformative negative means that the lab looked through all of the letters in the gene(s) that were tested and did not find any mutations (harmful spelling errors or missing/extra letters). An uninformative negative genetic test result means that the chance for a strongly genetic cause for the cancer in your family is likely low but not zero.

With an uninformative negative genetic test result, it is important to interpret that result in the context of the family history. It is possible that a gene mutation is responsible for a family history of cancer, but it was just not passed down to the individual that was tested. It is also possible that there could be a mutation in the genes that were examine that cannot be found by our current technology. New genes related to an increased hereditary cancer risk are continually being discovered, so there is the potential that there could be a gene that is increasing the risk in a family that we just have not found yet.

Because of all of this, even if someone has an uninformative negative genetic test, if they have a strong family history of cancer they still may have an increased risk. If genetic testing is negative, we determine someone’s risk as well as screening and management guidelines based on their family history.

If there is already a known mutation in the family and testing does not identify that mutation, this is considered a true negative result, which rules out the increased cancer risks associated with that known mutation. Unless other, unrelated risk factors are identified in the history, screening and management recommendations are based on general population guidelines. Further, any children of an individual with a true negative result are not at risk to inherit the mutation and testing for them is not necessary (unless they have a suspicious history of cancer on the other side of their family).

My Results Say I Have a Variant of Uncertain Significance - What does that mean?

A variant of uncertain significance (VUS) is when the lab found a spelling change (by sequencing) or a missing or extra piece (by deletion/duplication studies), but are not entirely sure what it means.

Most of the time, researchers get more information about the VUS and find that it is not linked with an increased risk for cancer. The majority of VUS findings are spelling errors or extra/missing pieces in the gene that don’t change the instructions, and thus do not affect the protein that the gene makes.

An example would be the sentence A CAT RAN. A VUS would be similar to if the sentence said A CAT RUN instead of A CAT RAN. The spelling error that changes RAN to RUN makes the sentence not make grammatical sense, but it doesn’t change the overall meaning of the sentence.

In some cases, research studies can be offered to family members to help determine whether the spelling error or missing/extra piece is harmful or not, but it can take months to years to reach more definitive answers. Due to the uncertainty of a VUS result, testing of other family members for the variant is not usually recommended outside of research studies. Until the result can be clearly interpreted as a positive or negative, cancer risk and screening would be based on the individual and/or family history of cancer.

There are several reasons why someone may consider genetic testing for hereditary cancer predisposition, which are outlined below.

High-Risk Screening and Risk Management

One of the primary benefits of knowing about hereditary cancer risk is the ability to take control of that risk in partnership with your healthcare team. Genetic testing and clarification of hereditary risk for cancer helps to guide recommendations and decisions for appropriate medical management, cancer screening, and cancer prevention approaches. High-risk cancer screening may include earlier and/or more frequent screenings to try to detect cancer at the earliest, most treatable stages. Surgery or medications may also be available to reduce the overall risk of developing cancer. Specific recommendations should be discussed with your providers.

Potential to Rule Out Increased Risk

If the cancers in a family are caused by a known mutation, and testing rules out that mutation in a family member (a true negative result), then his or her cancer risk should be no greater than the population risk and high-risk screening is no longer necessary. Further, his or her children would also not be at risk for the mutation.

Cancer Treatment Decisions

As our understanding of the relationship between genetics and cancer expands, so does the range of cancer treatment options. Many new cancer treatments are being studied and developed to target particular types of genetic mutations found in cancers (both inherited and not inherited). This important work is helping to make treatments more personalized and effective.

Further, individuals with hereditary cancer risk may be at higher risk to develop a second cancer in the future. In planning the treatment course for a current diagnosis, knowledge of genetic risk may influence decisions about the type or extent of current treatments (for example, some people may consider more extensive surgery, such as bilateral mastectomies, to remove the current tumor as well as prevent the development of a future cancer). Also, some mutations are known to cause increased sensitivity to treatment-related side effects (such as radiation-induced damage), which may guide the treatment plan toward safer approaches.

Information for Family Members

For individuals who already have a diagnosis of cancer, another common concern is the implications for the health of loved ones. Genetic testing is most helpful when first performed in an individual who has had the cancer of concern (if a mutation exists in the family, this is where testing is most likely to positively identify it). If a causative mutation is identified, then testing of at-risk family members becomes much more straightforward to definitively confirm or rule out the associated cancer risks. If, on the other hand, testing does not confirm hereditary risk in a person with the cancer of concern, then further testing of family members is not usually recommended or useful, and family members should be followed based on the history of cancer in the family.

Genetic testing for cancer risk is a very personal decision, and is not right for everyone. Some people are concerned about the benefits versus potential risks, while others are more concerned with insurance or privacy issues. Click below to learn more about these common concerns pertaining to genetic testing:

If genetic testing is performed but does not identify a harmful genetic variant, or if testing is declined for any reason, DNA banking is another resource available to ensure the ability for future genetic testing of one’s DNA. This is primarily for the benefit of family members, and can allow for the most informative genetic testing and interpretation in the family (since it is always recommended to start testing in a family member who has had the cancer of concern). DNA banking is available through many laboratories throughout the country at relatively low cost, and can be facilitated by your genetic counselor or other providers. If you pursue DNA banking, it is important that you keep copies of the paperwork and inform your family members of this resource for them.

Do you have concerns about your cancer risks?

A Personalized Cancer Risk Assessment can help you understand your risks. Get answer to FAQ's about the assessment or schedule an appointment, in-person or via telehealth.

Hereditary Cancer Predispositions

Cancer is a complicated disease, and often several factors, including genetics, environmental factors (such as exposures to toxins and/or chemicals), and lifestyle can impact your risk. There are some common hereditary cancer predispositions, though. Genetic counseling and testing can help you understand your hereditary cancer risk.

Breast cancer is a complicated disease, and there is no single explanation for it. In the vast majority of breast cancer, the cause is likely some genetics, some environmental factors (such as exposures to toxins and/or chemicals), and a lot of it is just bad luck. In most cases we are not able to pinpoint a specific cause, likely because in most cases there is not ONE specific cause to be found, but rather a combination of many different things coming together.

Some factors known to increase the risk for breast cancer are:

Gender

Breast cancer is almost 100 times more common in women than in men.

Age

The risk for breast cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older.

Race

Breast cancer is diagnosed more often in Caucasian women than in women of other races. However, African American women have a poorer survival rate compared to white women once diagnosed with cancer. This inequality may be due, in part, to differences in the availability of care and not necessarily genetic risk factors.

Family history

A family history of breast cancer increases a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer. How many people are affected in her family, how old they were when they were diagnosed, and how closely they are related to her will all influence how much the risk for cancer is increased.

Reproductive/hormonal history

Having no children, having your first child later in life, early menstruation (before age 12), and late menopause (after age 55) all increase the lifetime risk for breast cancer. This is primarily due to one’s exposure to estrogen over their lifetime.

Previous history of breast cancer

Women diagnosed with breast cancer in one breast have an increased risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer in the other breast in the future.

Certain benign (noncancerous) breast findings

Women with these findings, such as lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), can increase the lifetime risk for breast cancer.

Dense breast tissue

This may increase the risk for breast cancer, and also makes detection more difficult.

Lack of physical activity

Not getting enough exercise has been linked to an increased risk for breast cancer.

Alcohol consumption

The more alcohol that someone drinks, the higher their risk for breast cancer goes up. Most current studies recommend women limit their intake to no more than one serving of alcohol a day, but even this amount can increase breast cancer risks, as alcohol can affect estrogen levels in the body.

Obesity or being overweight

Individuals with a higher than average proportion of body fat have an increased risk for breast cancer, as well as decreased survival rates after diagnosis.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

HRT involves taking female sex hormones after menopause when a woman’s ovaries stop normal hormone production. This can involve either just taking estrogen, or taking a combination of estrogen and progesterone, and have been found to cause an increased risk for breast cancer.

Hereditary predisposition

Approximately 5-10% of breast cancers are part of a hereditary cancer syndrome. Mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are the most common and well known cause for inherited breast cancer risk, but mutations in other genes have also been identified to increase the risk for breast cancer. The below links include more information about hereditary breast cancer genes:

- Hereditary Breast & Ovarian Cancer syndrome (BRCA1/2)

- ATM-related Breast Cancer

- Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (CDH1)

- CHEK2-related Breast Cancer

- NBN-related Breast Cancer

- Neurofibromatosis, type 1 (NF1)

- PALB2-related Breast Cancer

- PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome (PTEN)/Cowden syndrome

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11)

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53)

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Is prostate cancer genetic?

Prostate cancer is unfortunately a relatively common disease, with 1 in 9 men diagnosed in their lifetime. Most of the time, cancer is caused by chance. Sometimes multiple factors play a role. In some families, cancer is caused by a single genetic factor that puts a man at a higher risk. called a hereditary predisposition.

What does my prostate cancer diagnosis mean for my family members and their chance to develop cancer?

Even though prostate cancer is quite common amongst men, most of these cancers are not considered to be hereditary. For those families that are found to have a hereditary cause, genetic testing allows for family members to be tested to see if they have a higher risk to develop cancer. No gene confers a guarantee that someone will go on to develop cancer. Men who have a family history of prostate cancer are still at an increased risk to develop this type of cancer even without an identified gene. Those family members that are at a higher risk of cancer can develop a personalized screening and cancer prevention plan with their doctors to help keep them healthy.

Does my doctor need to know if my prostate cancer is genetic?

We know that prostate cancer that is hereditary behaves differently than sporadic prostate cancer. If a man is found to carry a gene that strongly contributed his cancer, his doctors may discuss additional treatment options available to him to treat or stabilize the disease. This may be particularly important in men who have metastatic prostate cancer (cancer that has spread outside of the prostate to the bone or other organs).

Do only my sons need to worry about hereditary prostate cancer?

While sisters and daughters would not be at an increased risk for prostate cancer, many of the genes that cause prostate cancer in men (such as BRCA1 and BRCA2) are linked to higher risk of breast cancer or ovarian cancer in women. By testing for these genes, women can better protect themselves from these cancers.

How can I learn more?

Speaking with a genetic counselor is a great way to learn about hereditary prostate cancer. Genetic counseling involves a discussion about your cancer history and your family health history to assess the likelihood that there is a strongly hereditary contributor to cancer. A genetic counselor can also coordinate genetic testing for genes linked to hereditary prostate cancer. Whether you decide to have genetic testing or not, a genetic counselor can always help to counsel you and your family members about their chance to develop cancer…. and most importantly what they can do about it.

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Approximately 4.3% of people will be diagnosed with colon cancer during their lifetimes. There are many different causes and risk factors for developing colon cancer, including genetics, environment, and chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of colon cancers cannot be identified. Rather it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer. The good news is that screening for colon cancer is highly effective in reducing the frequency and severity of colon cancer, both in the general population as well as for persons with a hereditary risk.

Some factors known to increase the risk for colon cancer are:

Demographics

- Age: the risk for colon cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older.

- Race: data has shown that African Americans have increased risk to develop colon cancer, as well as increased incidence of deaths from colon cancer. The reasons for these differences are not fully understood, but may in part be due to differences in access to screening for colon cancer.

Lifestyle/Environmental Factors

- Alcohol consumption: three or more drinks of alcohol per day has been associated with elevated risk for colon cancer.

- Cigarette smoking: smoking has been implicated as a risk factor for multiple different cancers, including colon cancer.

- Obesity

Personal Medical Factors

- Previous history of colon polyps: a history of colon polyps, specifically adenomatous polyps or sessile serrated polyps, indicates increased risk for future polyps and/or cancer if the polyps are not sufficiently managed.

- Previous history of colon cancer: individuals with a history of colon cancer are at increased risk not only for recurrence of that cancer, but for development of a second cancer.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease): chronic inflammation of the colon tissues can damage the cells and, over time, can lead to cancerous changes in the colon tissue.

Family History

- Family history of colon cancer or advanced adenomatous polyps: how high the risk is depends on how many relatives have been diagnosed, how closely you are related to the family members who have been diagnosed, and how old those relatives were when they were diagnosed.

- Hereditary cancer syndromes: approximately 5-10% of colon cancers are due to inherited genetic mutations which increase the risk for colon cancer. Several different genes and genetic syndromes are known to be associated with increased risk for colon cancer. The links below provide more information about hereditary colon cancer genes.

Genes related to an increased risk for colon cancer:

- Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, PMS2, MSH6, and EPCAM)

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (APC)

- AXIN2-related Colon Cancer

- GREM1-related Colon Cancer

- Juvenile Polyposis syndrome (BMPR1A, SMAD4)

- MSH3-related Colon Cancer

- MUTYH-Associated Polyposis

- NTHL1-related Colon Cancer

- POLD1-related Colon Cancer

- POLE-related Colon Cancer

- PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome (PTEN)/Cowden syndrome

- Serrated Polyposis syndrome

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11)

- Li Fraumeni syndrome (TP53)

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Gastric (stomach) cancer occurs in less than 1% (0.8%) of people in their lifetimes. Known environmental and genetic risk factors for gastric cancer include:

Demographics

- Age: the risk for gastric cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older.

- Gender: gastric cancer occurs more frequently in men than in women.

Lifestyle/Environmental Factors

- Diet: eating a diet rich in salted and smoked foods, and deficient in fruits and vegetables, can increase the risk for gastric cancer.

- Cigarette smoking: smoking has been implicated as a risk factor for multiple different cancers, including gastric cancer.

- Occupation: people who work in the rubber and coal industries appear to be at elevated risk for gastric cancer.

Personal Medical History

- Infection with H. pylori

- Gastric polyps

- Chronic inflammation of the stomach (gastritis)

- Pernicious anemia

- Intestinal metaplasia

Family History

- Family history of gastric cancer: how high the risk is depends on how many relatives have been diagnosed, how closely you are related to the family members who have been diagnosed, and how old those relatives were when they were diagnosed.

- Hereditary cancer syndromes: approximately 3-5% of gastric cancers are due to inherited genetic mutations which increase the risk for gastric cancer. Several different genes and genetic syndromes are known to be associated with increased risk for gastric cancer. The links below provide more information about hereditary gastric cancer genes.

Genes related to an increased risk for gastric cancer (click on them for more information):

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (APC)

- Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (CDH1)

- Juvenile Polyposis syndrome (BMPR1A, SMAD4)

- Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, PMS2, MSH6, and EPCAM)

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11)

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Uterine/Endometrial Cancers

Approximately 2.7% of women will be diagnosed with uterine cancer (cancer of the womb) during their lifetimes. There are many different causes and risk factors for developing uterine cancer, including genetics, environment, and chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of uterine cancers cannot be identified. Rather it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer.

Some factors known to increase the risk for uterine cancer are:

Demographics

- Age: the risk for uterine cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older. Most women with uterine cancer are diagnosed after menopause.

- Race: Uterine cancer is slightly more common in white women compared with other races.

Lifestyle/Environmental Factors

- Obesity: Obesity is a well known risk factor for uterine cancer. Studies have also shown that a high-fat diet can increase the risk of several cancers, including uterine cancer

- Sedentary lifestyle: Women who exercise more have a lower risk of uterine cancer

Hormonal Factors

- Estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HRT): Estrogen-based HRT taken after menopause can increase a woman’s risk of uterine cancer. To lower this risk, a second hormone called progesterone is usually taken at the same time as estrogen replacement. This is called combination hormonal therapy, and it has not been shown to increase risk of uterine cancer.

- Number of menstrual cycles: Women who start their periods at a young age (prior to age 12) and/or enter menopause at a late age (after age 55) have a higher risk of uterine cancer

- Pregnancy: Women who have never been pregnant have a higher risk of uterine cancer

Personal Medical Factors

- Diabetes: Women with diabetes are 4 times as likely to develop uterine cancer

- Tamoxifen: Pre-menopausal women who take tamoxifen to treat or prevent breast cancer have an increased risk of uterine cancer

- Polycystic Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (PCOS): The hormonal imbalances associated with PCOS can result in an increased risk of uterine cancer

- Endometrial atypical hyperplasia: increased atypical growth of the endometrium (lining of the uterus) can turn into uterine cancer. Mild or simple hyperplasia is rarely associated with uterine cancer.

- Prior pelvic radiation: Radiation treatment for a prior cancer can damage nearby cells are increased risk for a new cancer

Family History

- Having a close relative who has been diagnosed with uterine cancer increases a woman’s risk to develop the same type of cancer. This is likely due to a combination of shared environmental and genetic factors (see Family History).

- Some families have a very strong predisposition to uterine cancer called Lynch syndrome. Another name for Lynch syndrome is Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer syndrome (HNPCC), which also increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

A small number of all uterine cancers are due to a genetic reason such as Lynch syndrome. However, families that show multiple relatives with uterine or colon cancer, early onset (under age 50) of uterine cancer, or being diagnosed with a new primary cancer multiple times may want to consider genetic counseling and possibly genetic testing for Lynch syndrome.

There are other less common hereditary predispositions to uterine cancer associated with other genes such as PTEN (Hamartoma Tumor syndrome/Cowden syndrome), TP53 (Li Fraumeni syndrome), STK11, and POLD1 (polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis syndrome).

Cancer Screening and Prevention

If you have risk factors for endometrial cancer, it is important to discuss this with your gynecologist so that they can discuss warning signs and screening options. Healthcare providers may offer regular exams or ultrasounds of the pelvis to look for any concerning changes in the uterus/womb. Sometimes biopsies are used to see if these changes are cancerous even at an early stage. Finally, women at high risk of uterine cancer may be eligible to have their uterus removed through surgery to prevent a cancer (called a prophylactic hysterectomy).

Ovarian Cancer

Approximately 1 in 78 women (about 1.2%) will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer during their lifetimes. There are many different causes and risk factors for developing ovarian cancer, including genetics, environment, and chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of ovarian cancers cannot be identified. Rather it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer.

There are three different types of cells within the ovary. Germ cells produce eggs, stromal cells produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone, and epithelial cells cover the surface of the ovary. There are many types of ovarian tumors in all three types of cells which can be benign or malignant (cancerous), however the majority of malignant ovarian cancers (90%) begin in the epithelial cells (called carcinomas).

Some factors known to increase the risk for this more common epithelial ovarian cancer are:

Demographics

- Age: The risk for ovarian cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older and most are diagnosed in women who have entered menopause

- Race: Ovarian cancer is more common in white women

Hormonal Factors

- Estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HRT): Estrogen-based HRT taken after menopause can increase a woman’s risk of ovarian cancer when taken for a long period of time (at least 5-10 years). It is unclear if women who take HRT of estrogen combined with a second hormone called progesterone at the same time are also at increased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Pregnancy: Women who have their first full-term pregnancy after age 35 or have never been pregnant have a higher risk of ovarian cancer

Unclear Risk Factors

- Androgen hormones: Exposure to male hormones like testosterone appear to be linked to certain types of ovarian cancer however more studies are needed

- Talcum powder: There have been conflicting studies about whether there is a link between talcum powder and a higher risk of ovarian cancer. In those studies that show an increased risk of ovarian cancer, the overall increase is thought to be relatively small.

Family History

- Having a close relative who has been diagnosed with ovarian cancer increases a woman’s risk to develop the same type of cancer. This is likely due to a combination of shared environmental and genetic factors (see Family History).

- Some families have a very strong predisposition to ovarian cancer due to a genetic factor. In fact, up to 25% of all ovarian cancers are attributed to a hereditary cause and because of this high prevalence, all women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer are recommended to undergo genetic testing. There are multiple well known genetic syndromes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer:

- Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (HBOC) due to mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes

- Lynch syndrome (also known as Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer), which increases the risk for uterine, ovarian, and colorectal cancer, among others.

- Peutz Jeghers syndrome

- RAD51C-related Ovarian Cancer

- RAD51D-related Ovarian Cancer

- BRIP1-related Ovarian Cancer

Cancer Screening and Prevention

If you have risk factors for ovarian cancer, it is important to discuss this with your gynecologist so that they can discuss warning signs and screening options. Healthcare providers may offer regular exams or ultrasounds of the pelvis to look for any concerning changes in the uterus/womb. Blood tests to look for a marker of ovarian cancer (called CA-125) can also be used, but as of now the combination of pelvic ultrasounds and blood tests has not been shown to be an effective method of diagnosing ovarian cancer at an early stage.

Women at high risk of ovarian cancer may be eligible to have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed through surgery to prevent a cancer (called a prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Many ovarian cancers are thought to originate in the nearby fallopian tubes, so it is recommended to remove the tubes along with the ovaries.

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

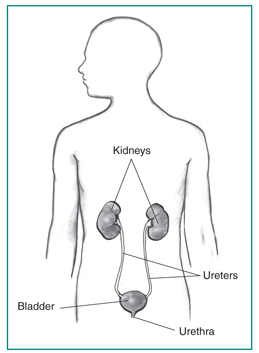

Urinary tract cancers are cancers that affect primarily the kidneys or the bladder, which work to filter out and get rid of waste products that our bodies produce. These forms of cancer will affect approximately 5-6% of all men and 2-3% of women during their lifetimes. Although the kidney and bladder work together to perform their functions, there are many differences between them.

Kidney Cancer

Approximately 2% of men and 1.2% of women will be diagnosed with kidney cancer during their lifetimes. The most common type of kidney cancer is called renal cell carcinoma. There are several subtypes of renal cell carcinoma that are characterized by the way the cells look under a microscope. Each subtype provides information about treatment options for patients but also information about whether a particular type of kidney cancer is more likely to be hereditary:

- Clear cell subtype: 70% of renal cell carcinomas

- Papillary subtype: 10% of renal cell carcinomas

- Chromophobe subtype: 5% of renal cell carcinomas

- More rare and unclassified renal cell carcinomas make up the remaining subtypes

Renal pelvic cancers make up 5% of kidney cancers and occur in the lining where the ureters attach to the kidney. Because these cancers look like bladder cancer under the microscope, they are often called transitional cell carcinomas.

Sarcoma of the kidney is rare and can occur in the blood vessels or connective tissue.

Wilms tumor is a type of kidney cancer that nearly always occurs in children, and have been associated with other genetic syndromes.

Finally, there are benign tumors of the kidney. While not cancerous, they can sometimes cause medical problems and may require intervention. Examples include: renal adenomas, angiomyolipomas, and oncocytomas.

Risk Factors for Kidney Cancer

There are many different causes and risk factors for developing kidney cancer, including genetics, environment, and random chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of these cancers cannot be identified. Rather, it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer.

Demographics

- Age: the risk for kidney cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older.

- Race: Kidney cancer is slightly more common in African Americans and Native Americans.

- Gender: Compared with women, men are two times more likely to develop kidney cancer

Environmental

- Smokers are at a higher risk of kidney cancer than non-smokers.

- Obesity: Being overweight is a risk factor for many cancers, including kidney cancer.

- Chemical exposure: Exposure to specific organic solvents and the metal Cadmium have been linked to a higher risk of kidney cancer.

- Medications: A pain medication that was available decades ago called phenacetin has been linked with kidney cancer. Diuretics (water pills) are also a possible risk factor for kidney cancer.

Medical History

- High blood pressure: Individuals with high blood pressure are at a higher risk of kidney cancer. Some medications used to treat high blood pressure have also been suspected to increase risk of kidney cancer.

- Individuals with advanced kidney disease requiring dialysis are at increased risk of kidney cancer.

Family History

- Having a close relative diagnosed with kidney cancer increases one’s chance to develop kidney cancer themselves. This may be due to shared genetic risk factors but also shared environmental risk factors.

Hereditary Kidney Cancer

It is estimated that 5% of kidney cancers are due to a hereditary cause. Individuals with bilateral or multifocal renal cell carcinoma or kidney cancer that is early onset (diagnosed at age 46 or younger) should consider genetic counseling. Certain subtypes of renal cell carcinoma are more commonly hereditary, such as papillary, chromophobe kidney cancers or oncocytic kidney tumors. Syndromes associated with hereditary kidney cancer include:

- Von Hippel Lindau

- Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma (Reed’s Syndrome)

- Tuberous Sclerosis

- Birt-Hogge-Dube syndrome

- PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome/Cowden syndrome

- Hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma

- Papillary Renal Neoplasia

- Adrenal gland cancers

Bladder Cancer

1% of women and 3.7% of men will develop bladder cancer. Nearly all bladder cancers begin in the lining of the bladder and are called urothelial carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma. Rarer subtypes of bladder cancer include adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and sarcoma.

Risk Factors for Bladder Cancer

There are many different causes and risk factors for developing bladder cancer, including genetics, environment, and chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of these cancers cannot be identified. Rather it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer.

Demographics

- Age: the risk for bladder cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older.

- Race: Whites are at a slightly higher risk of bladder cancer when compared to Blacks and Hispanics.

- Gender: Compared with women, men are three to four times more likely to develop bladder cancer.

Environmental

- Tobacco use: Cigarette smoke is considered to be one of the strongest risk factors for bladder cancer and is thought to cause as many as 50% of these cancers. Smokers are three times as likely to develop bladder cancer compared with non-smokers.

- Chemical exposure: Chemicals used in the dye, rubber, leather, textile, paint, printing, hairdressing, and truck driving industries have been associated with a higher chance of developing bladder cancer. Arsenic in drinking water is a risk factor for bladder cancer, but this is not a major source of risk in most Americans.

- Medications: The herbal supplement aristolochic acid has been linked with bladder cancer. There is some evidence that pioglitazone (brand name Actos), a medication used to treat diabetes, is associated with a higher risk of bladder cancer.

Medical History

- Chronic bladder infections, bladder stones, and kidney stones are linked with a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder

- Rare birth defects, specifically involving the urachus or a condition called exstrophy, may be the cause of some bladder cancers.

- Chemotherapy: Treatment with the drug Cytoxan can irritate the bladder and put someone at a higher risk of bladder cancer

- Previous radiation to the pelvis puts an individual at increased risk of bladder cancer

Family history

- Having a close relative diagnosed with bladder cancer increases one’s risk to develop the same disease. This may be because relatives are exposed to the same environmental risk factors (see Family History).

Genetics

Bladder cancer alone is not known to be caused by a single genetic factor, however there are some hereditary cancer syndromes that have been possibly associated with a higher risk of bladder cancer in addition to an increased risk of other cancers. These include:

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

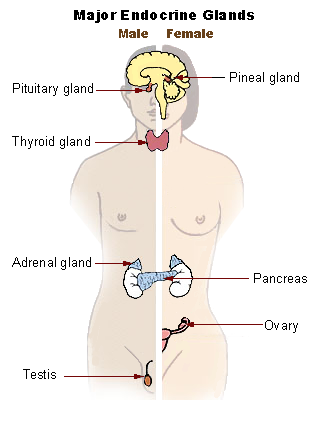

The endocrine system is responsible for producing and managing the hormones that regulate many parts of the human body. Most of the tumors that affect the endocrine system are benign (non-cancerous) but they can still have a major effect on a person’s health. Compared with other types of cancer, endocrine cancers are much less common. However, a greater proportion of endocrine cancers can potentially be hereditary.

Some factors known to increase the risk for endocrine tumors are:

Lifestyle factors

Maintaining a healthy weight and being physically active can reduce the chance that someone develops cancer.

Smoking

It has been suggested at smoking cigarettes increases an individual’s chance of adrenal cancer and pancreatic neuroendocrine (islet cell) tumors.

Age and gender

Thyroid cancer is more common in women than in men and is more common in middle age (40s and 50s). Men are more likely to develop pheochromocytomas than women.

Iodine

Diets low in iodine increase an individual’s chance to develop thyroid cancer, however this is less common in countries with iodine added to their foods, such as the United States.

Diabetes

Individuals with diabetes are at an increased risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine (islet cell) tumors.

Radiation Exposure

Children who have been treated with radiation to the head or neck are at an increased risk of thyroid cancer. Imaging tests such as X-rays and CT scans expose individuals to a small dose of radiation. While this amount is generally safe, these tests should only be used when needed to prevent unnecessary radiation exposure. Studies have determined that individuals exposed to nuclear radioactive material from accidents at nearby power plants or nuclear weapons are also at increased risk of thyroid cancer.

Types of Neuroendocrine tumors and Cancers

The varieties of endocrine tumors and cancers are very diverse and can occur in any part of the endocrine system:

- Thyroid

- Parathyroid (Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia, type 1)

- Pituitary

- Adrenal (Paraganglioma and Pheochromocytoma)

- Pancreatic (Islet cell)

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Approximately 1.5% of individuals will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer during their lifetimes, making it overall fairly rare. There are many different causes and risk factors for developing pancreatic cancer, including genetics, environment, and chance. As with most cancers, a specific cause for the great majority of pancreatic cancers cannot be identified. Rather it is likely that there are multiple factors which play a part in the development of the cancer.

Ninety-five percent of pancreatic cancers occur in the exocrine cells (called pancreatic adenocarcinoma). A less common type of pancreatic cancer affects the hormone-producing cells, called islet cells, and is referred to as a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET).

Some factors known to increase the risk for pancreatic cancer are:

Demographics

- Age: the risk for pancreatic cancer (and most other cancers) increases as we get older. The average age of diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is age 71.

- Race: African Americans are at slightly increased risk of pancreatic cancer

- Gender: Men are slightly more likely than women to develop pancreatic cancer

Environmental Factors

- Tobacco use: Cigarette smoke is considered to be one of the strongest risk factors for pancreatic cancer and is thought to cause as many as 30% of these cancers. Smokers are twice as likely to develop pancreatic cancer compared with non-smokers. Pipe smokers and smokeless tobacco is also linked to higher chance to develop pancreatic cancer.

- Obesity: Being overweight is a risk factor for many cancers, including pancreatic cancer.

- Chemical exposure: Chemicals used in the dry cleaning and metal working industries have been associated with a higher chance of developing pancreatic cancer.

Medical History

- Diabetes: Individuals with type II diabetes are at increased risk of pancreatic cancer. It is unclear if type I (pediatric-onset) diabetics are also at increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

- Pancreatitis: Chronic inflammation of the pancreas is a known risk factor for pancreatic cancer, particularly when a person is also a smoker; However, most people with pancreatitis still do not go on to develop pancreatic cancer.

- Cirrhosis: Scarring of the liver due to damage from chronic alcohol use or infection puts a person at increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori.) infection: This bacterial infection of the stomach as well as an increase in stomach acid may increase pancreatic cancer risk.

Factors like alcohol use, physical inactivity, coffee, and diets that are high in red meat and processed meats are all proposed risk factors for pancreatic cancer, however these are still being investigated to more fully understand their role.

Family History

Most people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer do not have a family history of this cancer, however it can appear to cluster within families. Having a close relative with pancreatic cancer can increase one’s chances of developing this disease, but this increase is likely small overall.

Genetic Predisposition Syndromes

As many as 10% of all pancreatic cancers may be due to a genetic risk factor and therefore it is recommended that all individuals with pancreatic cancer consider genetic counseling. Some hereditary predispositions to pancreatic cancer include:

- Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) syndrome (BRCA1/2)

- Lynch syndrome

- Familial Atypical Multiple Mole and Melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome

- Familial Pancreatitis, PRSS1

- Peutz Jeghers Syndrome

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

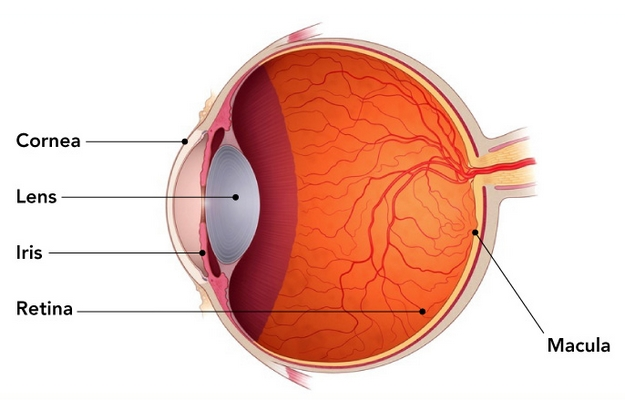

Retinoblastoma is rare cancer that starts in the retina. The retina is the region on the back of the eye which senses light and sends messages to the brain. Retinoblastoma most commonly occurs in early childhood. It may occur in one eye (unilateral) or in both eyes (bilateral). The first sign of this cancer is often leukocoria (the white reflection of light when looking at the pupil of the eye) or strabismus (one “crossed” or outwardly gazing eye).

Ninety percent of children diagnosed with retinoblastoma in one eye have no family history of this type of cancer. While for many of these children their cancer developed sporadically by chance, there is a possibility for each child diagnosed with retinoblastoma to have a genetic predisposition as the cause for their cancer. Because of this possibility, all children diagnosed with retinoblastoma should be offered genetic counseling to discuss the option of genetic testing. The likelihood of a genetic explanation increases if the cancer occurs in multiple spots within the same eye (multifocal), if the cancer occurs in both eyes, or there is a family history of retinoblastoma.

There are no external risk factors (such as cigarette smoking or alcohol exposure) that are confirmed to cause retinoblastoma.

Genetics and Inheritance

We have over 20,000 different genes in the body. These genes are like instruction manuals for how to build a protein, and each protein has an important function that helps to keep our body working how it should. Pathogenic (or harmful) variants in the RB1 gene cause hereditary retinoblastoma. The RB1 gene makes a protein called pRB. The pRB protein is a tumor suppressor, which means that it works in the body to make sure that cells do not grow out of control. When someone does not have enough of this pRB protein in their body, cells can grow out of control, which is what can lead to cancers like retinoblastoma.

Pathogenic variants in the RB1 gene are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that children of someone who carries a pathogenic variant each have a 50% chance to inherit the variant and associated cancer risks. Women and men both have the RB1 gene and have the same chances to inherit and pass down variants in these genes.

Genetic Testing for RB1

Genetic testing for pathogenic variants in the RB1 gene is currently available, but there are a few different ways to approach testing:

- Single site analysis: Testing specific to a known pathogenic variant in the family

- Full gene sequencing and rearrangement analysis: Comprehensive testing to search for all currently detectable variants in the gene

- Chromosome microarray: Testing that looks for missing pieces of chromosome 13 (which is where the RB1 gene is)

Risk of Cancer with RB1 gene mutations

Retinoblastoma

The majority of individuals who inherit a pathogenic variant in the RB1 gene will develop cancer in both of their eyes. Fortunately, retinoblastoma is usually curable when detected early. Retinoblastoma is most likely to occur within the first few years of life. Children who have a pathogenic variant in the RB1 gene should have surveillance under anesthesia every 3 – 4 weeks within the first 6 months of life. Children should then have an eye exam every 3-6 months until age 7. After age 7, these exams can be spaced out to every 1-2 years.

Pinealblastoma

Five and a half percent of people with pathogenic variants in the RB1 gene will develop a tumor in the “retina like” pineal gland of the brain (referred to a trilateral retinoblastoma). A regular MRI of the brain can be done for young children to screen for this.

Other cancers

There is an elevated risk of some cancers outside of the eye, including tumors of the bone (osteosarcoma) and the soft tissue of organs. The onset of these other cancers may be in childhood or adulthood. Because of this, regular total body MRI screening might be recommended for people with pathogenic variants in the RB1 gene.

Melanoma skin cancer also occurs more frequently in individuals with RB1 pathogenic variants, and a regular skin check is recommended.

People with a RB1 pathogenic variant have a sensitivity to radiation, so avoiding radiation therapy (CT scans and x-rays) unless absolutely necessary can be helpful to reduce the chance for a second cancer.

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Certain genetic conditions can increase the chances for affected people to develop tumors. These tumors may be linked to an increased risk for cancer, or could be non-cancerous tumors (benign). Benign tumors, while not significantly increasing the risk for cancer, may grow to larger sizes and affect how some organs or tissues in the body function. Some tumor predisposing genetic conditions may cause affected people to develop many tumors throughout their body, which can eventually lead to physical disfigurement.

Some genetic conditions known to predispose to developing tumors are:

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Neurofibromatosis, type 1

- Neurofibromatosis, type 2

- BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome

- DICER1 syndrome

- PTEN Hamartoma Tumor syndrome

Click here to learn more about scheduling a genetic counseling appointment for questions about hereditary cancer predisposition.

Have questions?

If you still have questions about hereditary cancer predisposition and what it means for your health, we encourage you to talk with one of our genetic counselors.

Cascade Screening Connector

Genetic Support Foundation has partnered with the Washington State Department of Health to provide cascade screening to help people identify and contact family members who may have an increased chance of developing cancer. This program is available to anyone in Washington state with hereditary cancer risk.

Cascase Screening Connector

Talking about hereditary cancer risk with family members can be complicated. Additionally, it can sometimes be difficult to identify and contact at-risk family members who might benefit from genetic counseling and any subsequent genetic testing. The Cascade Screening Connector can help.

Anyone in Washington state with hereditary cancer risk can call the Cascade Screening Connector at (360) 524-6577 or toll free at (800) 364-1641.

What is cascade screening?

Some genetic conditions can be passed from parent to child, generation to generation, affecting multiple family members. Cascade screening is a way to identify and test the relatives of people who have particular genetic conditions that may “run in the family,” such as Lynch Syndrome and Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome.

When a person is diagnosed with one of these conditions, their family members are at heightened risk for that condition too. Unlike some other genetic conditions, Lynch Syndrome and Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome are “autosomal dominant” conditions. This means there is a 50% chance of a parent passing on the condition to their child. That’s why it’s so important to talk with relatives about getting screened. Cascade screening gives health care professionals a chance to detect these conditions early and provide appropriate medical recommendations.

Relatives at risk commonly include first- and second-degree relatives such as parents, siblings, children, uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews, grandparents, grandchildren, and half-siblings.

How does the Cascade Screening Connector help?

The Cascade Screening Connector (CSC) is a new Washington State public health service. The CSC helps identify at-risk relatives and collect contact information, share the diagnosis with these relatives, and connect them with health services. A Cascade Screening Connector team member will walk you through your family tree to develop a plan for communicating this important information to the appropriate family members. For more information, visit: www.doh.wa.gov/CascadeScreening.

Additional Resources

The following resources can be used by patients and providers to share a diagnosis with family. Sharing this information is not always easy, but it is important and can even save lives.

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome

- Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome: A Guide for Patients and Their Families

- Sample Letter for Informing Your Family Members about Your BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation

- Sample clinician’s letter to provide patients to help them let their family members know about their BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation

- Where can I go to receive genetic services in Washington?

Lynch Syndrome

- Lynch Syndrome: A Guide for Patients and Their Families

- Sample Letter for Informing Your Family Members about Your Lynch Syndrome Mutation

- Sample clinician’s letter to provide patients to help them let their family members know about their Lynch syndrome mutation

- Where can I go to receive genetic services in Washington?

The Cascade Screening Connector service provided by the Washington State Department of Health helps connect family members who are at risk for hereditary cancer syndromes with appropriate health services.

AliveAndKickn is a nonprofit working to improve the lives of individuals and families affected by Lynch Syndrome and associated cancers through research, education, and screening.

The FORCE mission is to improve the lives of individuals and families facing hereditary cancer. Resources include peer navigation and expert-reviewed information.

This national research project brings patient voices into the healthcare experience and features video clips of people from a variety of backgrounds facing hereditary cancer.